June 27, 2025

The shame of the shame of the shame is the shame that who we are as we are is not enough. What we are not enough of is never clearly defined. If it were, it would be clear that who we are as we are is precisely enough.

There is one straightforward path to success, and it starts with healing shame. The trouble with shame is that addressing it often involves facing our shame, which can feel like shaming. For this reason, few people ever really heal their shame and experience the joy of life and the success that follows. By success, I am not referring to financial success, although financial success is a symptom of how much love we are willing to receive in return for the love we give through our labour and efforts. In the absence of shame, money flows more readily towards us. The success I am referring to is potentially available to all those who want love. To be in a healthy relationship with ourselves and others is the highest success we can achieve. It is a reflection of our heart and its willingness to accept ourselves and others as we are, free of shame.

Leaving Eden

The concept of being shame-free is poignant. Eden is where we are free of shame. Eden is in the arms of our mother at the moment of birth. Maturity is the departure from our mother’s arms, and it is the departure from Eden. If we succeed, we return to Eden through our love for ourselves and another exactly as we are. Acceptance liberates us from shame.

Despite the potential that comes with freeing ourselves from shame, it remains one of the least popular topics for humans to discuss. Most would rather do anything else than talk about their shame; occasionally, in the late hours, a few martinis might loosen lips only to retreat with the shame of the hangover that follows in the wake of sharing our hidden selves too freely. We all have shame to some degree; it is a feature of life. We experience guilt as something we did. We experience shame as something we are. The behaviours we adopt are curated to disguise the tender places we have found to store our shame, our true selves.

Eve’s Domain at the Esalen Institute

Shame will have us believe that the real version of ourselves, exactly as we are, is just not good enough, lovable enough, or perfect enough. Better we project that image onto those in the public domain, celebrities, politicians. Anyone it is acceptable to loathe or despise can be a safe place to project our shame. Our sense of shame is best described as helplessness in the face of something we need or want.

The opposite of shame is not pride; the opposite of shame is desire.

The seeds of shame find their roots in the arms of our mother and or our father when our needs are not met or met in an inconsistent way or in a way that frightens us. As a result, we cannot gain confidence that we can expect our desires and needs to be met. This shame is embedded in our psychic and somatic processes. Shame is a prison of the mind as much as it is a prison of the body. And this partly answers why it is so rarely talked about, there are few words to express what did not start as a cognitive process.

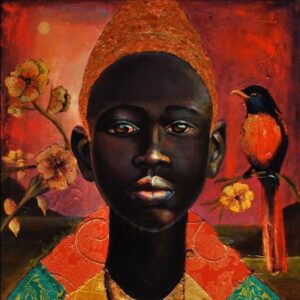

Childhood trauma resulting from parental violence can severely damage a child’s sense of belonging and fill them with a deep understanding of shame. This feeling of shame can often contribute to experiences of racism and exclusion as we grow older. It is not that the external world seeks to exclude us; we don’t feel worthy of being included.

Most people find a way to make a conversation about anything that touches on their shame disappear instead of addressing it. We are very good at creating elaborate tactics to alleviate the feeling of shame. Some will seek to find fault in another, thus shifting the burden of responsibility elsewhere. Some others will accuse you of shaming them. This way, they duck out of a rising sense of shame, a thermal glow across the cheeks, a pinching sensation in the chest, a trembling in the lips and around the mouth, sometimes the ears pound, a silent thunder caught in our throat, heart dances a Rhumba as the riptide of years of ancestral shame passed from one generation to the washes over our body. Mentally, shame is nearly always experienced as a disgust toward the self.

Because it is often such a deep wound, there are no meaningful quick-fix techniques for self-repulsion. Shame is often not in the cognitive part of who we are, so talking about it for an hour each week has limited effects. Shame resides in our earliest relationships, so the ultimate healing will occur in a supported space of loving tenderness, compassion, and care where it is possible for our whole body to feel and express the need, desire, or feeling that lives beneath the shame. This is why embodied therapeutic modalities are so effective. The memory of trauma in our body can be alleviated by creating a new memory, one of acceptance and love.

Racism, Oppression and Shame

Shame dissolves when it is brought into the light of our consciousness. When met with empathy and compassion, it melts like ice held in the soft arc of a warm hand. Imagine how different your life would be if you surrendered your attachment to holding onto shame.

Often, the shame does not belong to us. In Systemic Constellations, we can observe how shame is inherited and lovingly passed from one generation to the next. The following generation agrees to carry it out of loyalty, love and a need to belong. Racism is not an experience common to all, nor is it particular to people with darker skin. This is an example of how the trauma of shame interferes with our perception of reality. Racism is the expression of shame. The racist and the anti-racist find each other because they share the same wound. It is not unusual that once childhood trauma is addressed and an appropriate place has been created for family loyalties that support and uplift, the experience of racism fades or diminishes from our awareness. A good therapist will support you in holding this image in your heart. Many won’t or can’t because they have not attended to their own wounding and shame.

People who belong to oppressed groups and those who belong to groups that oppress others. I highlight these two groups simply because all humans alive today are descended from people who, at some point, belonged to both. The need to control and exclude those who don’t conform to a trauma-informed perception of the world is replaced with healthy connections to people and life.

Across the vast expanse of continents on Earth, millions live lives that they do not fully own because of shame. To a greater or lesser degree, we all have shame. We don’t all experience racism. Not all children are raised in violent environments or homes where shame is transmitted transgenerationally. Once children are protected from violence and a belief that they are worthless, racism will continue to decline. Discrimination is a slightly different matter; I will address it another time. For now, there is real-life value in addressing practical solutions to shame.

We can start by gifting future generations a model of the world informed by connections rooted in empathy and compassion.

The way out is through.

Those who find the courage to transcend shame discover something extraordinary: our success in life is determined by how true we are to our dreams and the truth of who we are. There is no other measure. To heal shame, we must be willing to face and be present with it. It may feel uncomfortable; however, it is nowhere near as painful as continuing to live with shame. It starts with finding sufficient courage to go to the heart of the matter, where our courage resides. Here, we discover what we may be holding there. As we shine a light on shame, it loses its power over us to keep us small. As shame is healed, creativity flows, and we flourish. This is the definition of success.

Here are a few things you can do to tune in to your shame:

1) Place your left hand over your heart. Close your eyes and take three deep breaths in through your nose and out through your mouth. Now, notice what happens when you ask yourself: “What is the need, desire or feeling beneath the shame?” Give yourself space and time to notice what thoughts, feelings, ideas and images come up.

2) You can use a journal to make notes and write down what you notice and experience. It’s a bit like a confession. It brings sweet relief!

3) When you have finished your exploration, offer yourself tender, loving kindness. “I deserve to be happy, safe, accepted and loved.” “It is my right to live free of pain and suffering.” “I am starting to see that I am a wonderful human being, worthy of love and kindness from myself and others.”

4) Feel free to message me and let me know how it went and what you experienced.