Belonging, Race and Inclusion

The Truth About Belonging

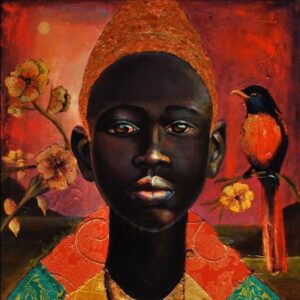

At our core, humans are social creatures. Our need to belong is not a social construct; it is biological. Other people matter to us in a way nothing else in the physical world can match.

That’s why we are wired to notice who feels familiar — who feels like us.

Certain parts of the brain activate when we imagine what others might be thinking or feeling. Do they share my faith? Would they understand my fears? Will they see me as safe?

Interestingly, these same brain regions aren’t involved when we notice physical traits such as height, weight, or skin colour. Which means our brains evolved to make social, not racial, distinctions.

Racism, then, is not an inevitable outcome of human nature. It is a construct — designed, marketed, and sold as fact. The truth is far more nuanced and far more human.

How We Were Trained to Misread Each Other

Belonging has always been mediated through class, religion, and culture — through the social codes that tell us who is “one of us.”

An educated Black man in a John Lewis suit is often more accepted in white middle-class circles than a white working-class man in Asda jeans. We see the same coded signals everywhere: the shoes worn to a BBC interview, the subtle inflections of accent that make an Oxford candidate seem “our sort.”

We have confused these social signals for something biological. We have taken a natural human instinct — the need to identify with those who feel familiar — and warped it into a system of division.

DEI teaches us to see race and gender as an identity. We are told it is ‘far right’ to identify people by race and gender.

When we behave as though all Black people think alike or that every Indian and Pakistani has moved beyond partition, we’re not being inclusive. We’re being lazy. We are denying complexity.

Human difference is not the problem. Our need to capitalise it is.

What Slavery Really Revealed About Belonging

Systemic Constellations reveal that belonging is rarely simple. Even in the darkest chapters of history, it forms complicated, often painful bonds.

Take plantation life

Modern narratives assume every day was an unrelenting horror. It is true that for many, the suffering was immense. But to survive, human beings formed attachments — however conflicted — with those around them. As in any family or workplace, there were loyalties, affections, dependencies, and betrayals.

Love is resilient. It exists inside conflict, sickness, and even oppression. What love cannot tolerate is exclusion.

When we simplify the history of slavery into a single story of victim and perpetrator, we eliminate the intricate human web that sustained life through unbearable circumstances. The truth is not comfortable, but it does bring us closer to healing.

The Economics of Division

Our social group — who we appear to belong to — often decides the treatment we receive:

a smile or a suspicious glance, a loan approved or denied, a promotion given or withheld.

This is not race at work. This is belonging — or its absence — playing out in everyday transactions.

Those who profit from maintaining division have long known this. They turned visual difference into hierarchy, hierarchy into policy, and policy into “race.” The illusion was so convincing that we began to believe it ourselves.

Academics and leaders have either failed to see through this illusion or benefited from it. Either way, the result is the same: separation and conflict disguised as truth.

The Real Story

Belonging is not defined by skin colour, nor is love.

It is shaped by age, gender, class, faith, sexuality, ability, and countless other markers of identity.

In Britain today, the most openly despised group is arguably the poor white working man — the one everyone else feels permitted to look down upon. Jean-Paul Sartre illustrated this kind of projection perfectly. A woman complains that her furrier is Jewish, as if that alone explains her dissatisfaction. Sartre asks: why not simply dislike the furrier? Why Jews?

When we need someone to blame, we reach for group identity. It feels easier, cleaner. But it’s also dishonest.

Belonging’s Double Edge

Belonging comforts and divides in equal measure.

To belong somewhere is to be excluded elsewhere. We each have a choice in how we participate in that exclusion — whether we reinforce it or question it.

In Systemic Constellations, we work to make these hidden loyalties visible. We look at how inherited ideas about who is “in” and who is “out” still govern our families, institutions, and our nations.

Because belonging is powerful.

It is the field through which love, inclusion, exclusion, and humanity all flow.

And when we see through the illusion of race — when we recognise belonging as the deeper truth — we begin to heal not only our families, but the world that shaped them.